Why The People?

Design Your Delta No. 10G

Guest Post by Ishani Chokshi

Ishani Chokshi is the first openly transgender student at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, working with Professor Alyson Carrel to develop the Delta Model for legal education.

My girls are not the type who go to lawyers. We don’t trust lawyers, we don’t respect the profession, and we recoil from any do-gooder lawyers who want to save us. And we have good reason: we’ve been burned too many times by legal insensitivity.

Transgender women - especially those of us of color - are all but excluded from theatres of law. The distance between the (mostly white, mostly male) profession of lawyers and my (mostly brown, mostly trans) girls remains vast. What exists is a cultural gap between our worlds, where mutual understandings fail to form and communications remain stale and strained. Only until I entered law school as a student - without any lawyers in my own family, and as the first (and at the time, only) openly transgender person in the school - did I begin understanding that this gap arises from our legal training itself.

Few legal professionals know how to talk to queer or brown people in general, how to deal with us, or how to advocate for us.

Law professors don’t know how to address us in class, and judges don’t know how to address us in courts. This is despite every clinic and firm rolling out praise for “the trans women of color in our community” when the June sun rolls around. Indeed, I must say that I too often feel like a prized fish to catch during this season, that my friends are trophies for legal professionals who seek to signal their good moral virtue through taking on pro bono cases and name-change clinics. Very rarely do I feel like I can speak to these lawyers in a way that is honest and open, human-to-human, with respect, dignity, and candor.

Unfortunately, many others entering the legal field (either as students, associates, or assistants) share my dilemma. Most non-white, non-male people in law schools have ample anecdotes to share about the racist, sexist, and generally insensitive and incompetent experiences we have had in our schools and practices, experiences we have largely learned to silently swallow and laugh about later. Indeed, lawyers’ social ineptitude is often a running joke in the broader culture. Even Lawyer’s Weekly loves a good lawyer joke.

But despite the good laughs which socially inept lawyers give us, the situation within the legal profession is grim.

Today’s law students are largely ill-equipped to meet the demands of an increasingly-diverse, increasingly-stressful market.

Law schools lack diversity both in the student body and in staff and faculty. Current legal practice is diseased, often quite literally, by rampant alcoholism, depression, and suicide within our ranks. Our colleagues are suffering and have hearts in pain.

For decades, researchers have pointed out that the legal profession placed too much emphasis on the traditional skills of “how to think like a lawyer” and not enough on skills related to communication and empathy. Some of this research resulted in significant buzz that is still discussed today. The fact stands, however, that our traditional frameworks are growing dusty. The growing demand to teach and build skills related to relationships, communication, empathy has led to deep rifts in legal academia between clinical/experiential/skills faculty and doctrinal faculty, but if COVID has taught us anything, it is that we need a new lens to evaluate our success as legal professionals in the global marketplace.

We need a pedagogical tool to prepare lawyers for our interconnected world.

Now, lots of good lawyers and good professionals have helped me and other trans women of color navigate schools, jobs, prisons, police, and homes. I ask, when we think about crafting a new pedagogy: can we learn something from these good apples? These legal professionals usually have great people skills, so what if “people skills” was part of the framework by which schools, firms, and associations evaluated legal competency?

What if humanist considerations were incorporated into the very fabric of legal pedagogy?

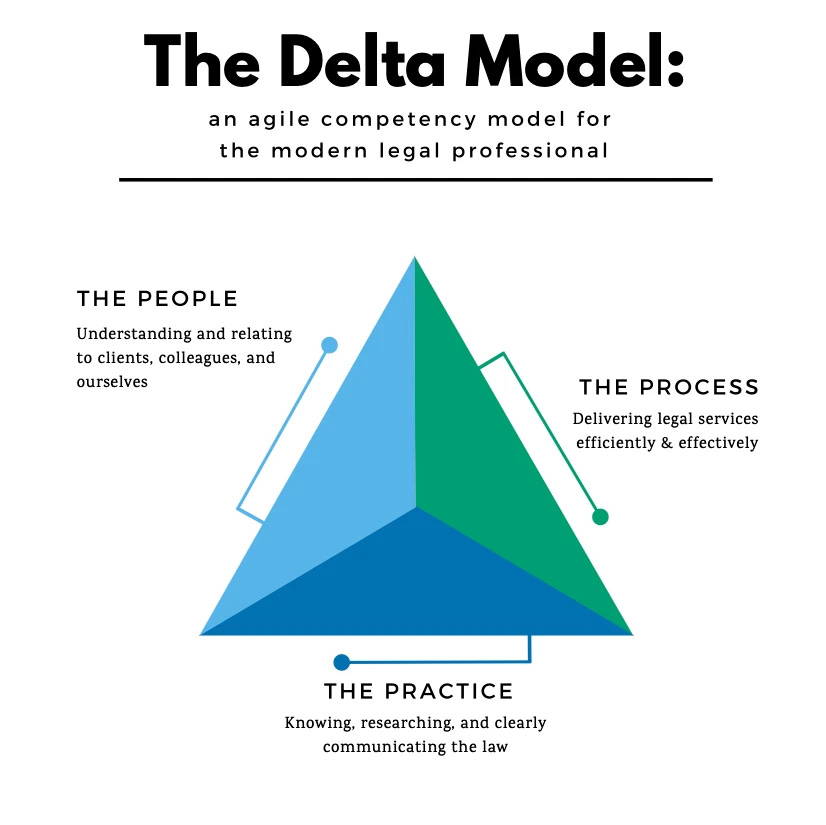

The Delta Model proposes to do just that. The Delta Model is visualized as a triangle with three general competency areas: The Practice, The Process, and The People. The left side of the triangle, “The People,” represents those skills that build relationships, demonstrate understanding, and enhance self-care. By identifying “The People” as one of the three major sides of the triangle, the Delta Model views the human component of lawyering (i.e. interviewing and counseling clients, becoming their trusted advisor, and managing one’s own wellbeing) as a critical component of the legal practice. In this way, the Delta Model promises to train lawyers of the future.

In the age of technology, where there are worries of lawyers being replaced by speedier robots, the Delta Model recognizes that human interactions will in fact become that much more important as a distinguishing value that humans provide when compared to some of the automated technologies. In COVID, we saw that with the rise in technology usage, legal professionals only increased the number of interactions we had with diverse peoples, both locally and globally.

Our lawyers need to learn to speak with the clients they serve, clients who are becoming increasingly diverse.

The Delta Model can bridge the fluency gap between lawyers and those they wish to serve. This fluency gap needs to be bridged quickly, not only so diverse peoples can feel comfortable around lawyers and get the help we need, but so that lawyers can become well-equipped to meet a global marketplace eager for people-friendly lawyers.

A few workshops and cultural trainings within schools and firms could go a long way in overcoming the steep learning curve many lawyers have in becoming more people-friendly with diverse clientele. And to truly overcome this learning curve, it is imperative that we embrace a new paradigm for our structures and institutions; and the Delta Model is waiting with open arms.

Written by Ishani Chokshi

Published by Alyson Carrel and Cat Moon

June 28, 2021