I listened in on an interesting conversation yesterday about efforts some corporate law firms are making to equalize how work gets assigned to associates. These efforts acknowledge that historically, work is often assigned ad hoc, leading to load imbalances, disparate opportunities, and favoritism. All of which supports the glaring lack of diversity at upper levels of seniority and leadership in corporate law.

Consider also the dearth of transparency and clarity around lawyer competencies across the legal industry, and it’s no surprise that work gets assigned in ways that promote the status quo, essentially devoid of meaningful diversity.1

Sponsored by the College of Law Practice Management,2 the conversation in question featured examples of experiments being conducted in North American law firms.3 I was heartened to hear about how these firms are leveraging transparency, communication, and data to create more equal opportunities for ALL lawyers.

And, I was struck by a few things. Ostensibly, creating ways to more clearly communicate who is available to do work, what kind of work they are qualified to do, and what kind of work they seek to do (out of interest, growth opportunities, etc.) should mean that firms can staff matters with greater equity. If focused on matching for skills and availability rather than primarily a senior lawyer’s personal preference, this could be a universal boon and lead to significantly more diverse representation at higher levels.

unintended consequences?

One thing that struck me: that these efforts could have unintended consequences, ones that are the opposite of stated outcomes to improve disparate work assignments. A primary way this can happen? When firms don’t start with a clear statement about what the competencies are for each level of associate/practice area/practice group (or however a firm organizes its working groups).

Absent agreement on — and communication about — the competencies expected and desired, any attempt at “matching” will be subject to the implicit bias that supports the status quo. A question worth asking: is it even possible to get lawyers to agree on a firm-wide (or even practice-group-wide) set of competencies that are communicated clearly and transparently to everyone?

Consider that senior lawyers often choose associates to work on their matters because those associates “do it the way I like it done” — they choose based on what they like, not based on a transparent assessment of an associate’s competencies set out against a well-defined standard.

This way of choosing masks implicit bias. If a program purports to be based on skills but isn’t grounded in a set of agreed-upon competencies, it provides cover, now under the guise of a “system” that the firm has adopted. Worth noting: there was a very short discussion about negative consequences if senior lawyers didn’t “get with the program” and use these new systems for assigning work. Prediction: there are no consequences. Senior lawyers have earned the right to organize their work the way they want to, and absent a very strong firm culture that forces compliance? There will be no consequences for those who forgo the system.

what it means to be data-driven

And, this brings me around to another thing I was struck by: how firms use (or don’t use) data for the purpose of supporting the growth and formation of their lawyers. All of the programs discussed offer an opportunity to surface data that could be used in very meaningful ways. Given that associate attrition rates are approaching 25% in US firms,4 leaders should be laser-focused on how they are designing cultures to attract and retain diverse associates.

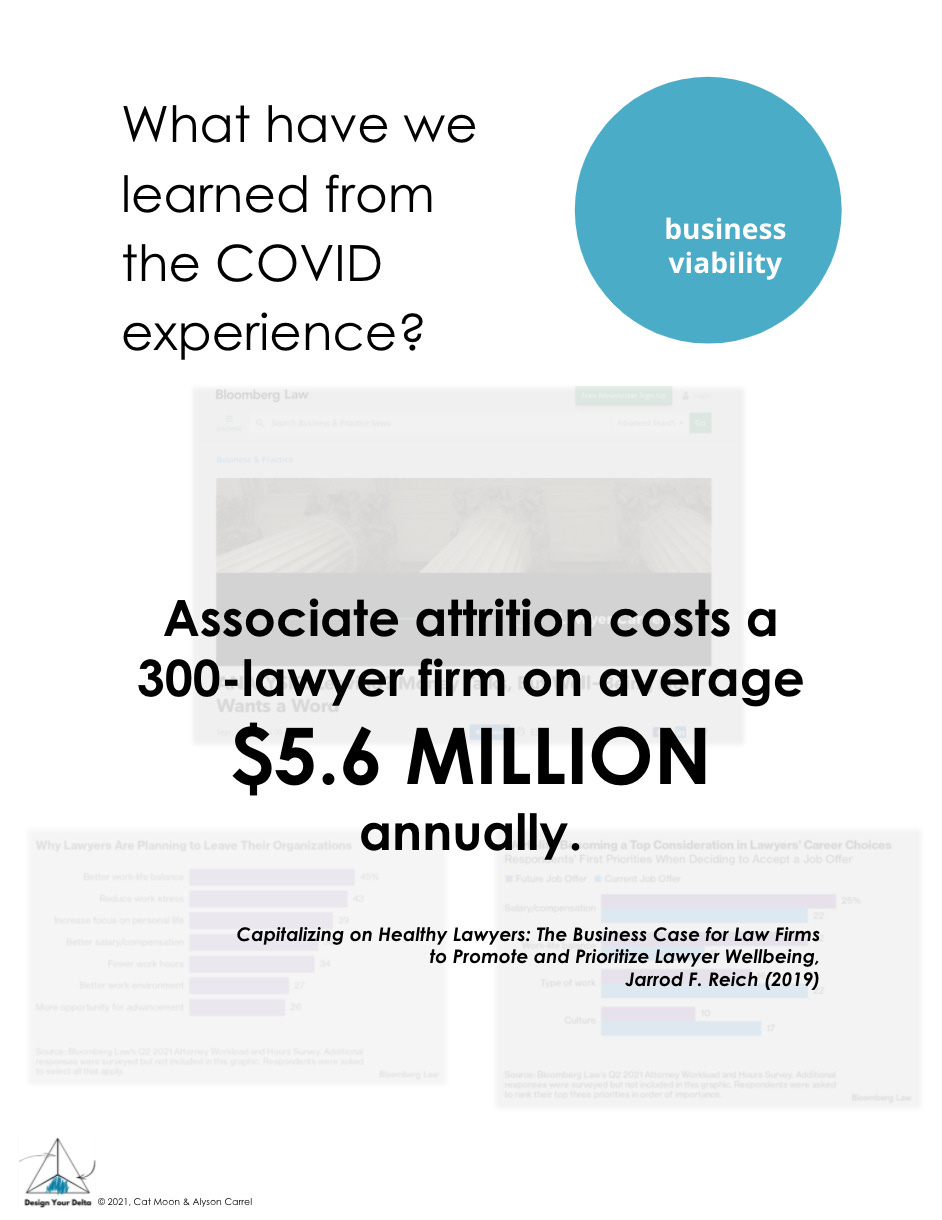

One calculation (that is probably low because of rising attrition rates over the past year): a 300-lawyer firm loses $5.6 million annually as a direct result of attrition.5 Law firm leaders should be losing sleep over how they can retain associates right now. If they aren’t, then their heads are buried too deeply in the proverbial sand.

If we start by clearly identifying and describing the competencies expected and desired, and we give associates meaningful opportunities to self-assess, develop self-awareness, and craft plans for professional growth and formation that account for these competencies and individual interests and preferences? We can create a combination workflow and professional formation system grounded in meaningful data.

We can collect the data, and use it for a myriad of purposes that if designed correctly, could refocus the over-emphasis on personal preference that currently defines how the work flows in most law firms.6 Data could be used to support the promotion of those who demonstrate competencies defined and described in ways not limited by partners’ personal preferences (and outright favoritism).

Another benefit, that goes directly to the attrition issue: we know that humans thrive when they have mastery and autonomy over their professional journey.7 We tend not to thrive in environments that deprive us of meaningful choices to learn and grow. A well-designed work assignment system could underpin this autonomy and support mastery as associates develop, by making transparent the competency expectations, and creating opportunities for associates to direct their own growth based not only on professional trajectories (and how these are defined by a firm) but also on their own interests and preferences.

The benefits are many and inure to all stakeholders. Because when associates thrive, the firm thrives (at least as long as leverage remains integral to the business model). Through the creation of transparent competency frameworks, everyone will benefit from the clarity created. This can counteract the prevalence of some benefiting from “unwritten” rules that exist in firm cultures where work is directed in opaque and preferential ways.

I’m not suggesting that using competency frameworks, whether by customizing a Delta Model for a certain role in a certain firm or using some other model, will magically solve the many problems we face in bringing resilient diversity, equity, and inclusion to the legal profession. I’ve been doing this work for nearly 25 years now and the only thing I know at this point: frameworks only work when people believe in them and use them. That law firm leaders will do so remains a very valid question.

I look forward to learning how the work assignment experiments in these firms evolve and hope they will serve as examples that other firms can turn to for inspiration. That they’re happening at all is a good thing. Perhaps even those intransigent partners will contemplate the impact of attrition on PPP and reconsider their instinct to work around the system.

- Cat

9 February 2022

See 2021 Profile of the Legal Profession (American Bar Association). A few fast facts: out of 1.3 million lawyers, 63% are male and 85.4% are white. In 2020, 87.8% of promotions from associate to equity partner were white lawyers, and 84.8% of promotions from associate to nonequity partner were white lawyers. The attrition rate of both black and hispanic associates in 2019 was 21%, compared to 11% for white associates. If you think that how work flows and is assigned in law firms has nothing to do with this? Think again.

Disclosure: I am a Fellow of the College of Law Practice Management (COLPM) and currently serve as a Trustee.

See 2022 Report on the State of the Legal Market (Thomson Reuters Institute and Georgetown Law Center on Ethics and the Legal Profession)

Another benefit: mapping associate competencies can support efficient and appropriate matter staffing in a way that our individual “preferences” simply cannot do. A competency map, like a customized Delta Map, reveals the full array of a lawyer’s competencies, and not simply the ones that a managing partner may have experienced. It also reveals those areas where a person seeks growth opportunities. Firms should be focused as much on how they create those growth opportunities as they are on exploiting existing competencies. If a firm isn’t, then it isn’t investing in its associates. And won’t reap the benefits.